“The only thing that will redeem mankind is co-operation… it is common to wish well to onself, but in our technically unified world, wishing well to onself is sure to be futile unless it is combined with wishing well to others.” Bertrand Russell

This quote from Bertrand Russell speaks to the widespread understanding that working collaboratively is to the benefit of all involved. In education there have been many initiatives aimed at capturing the power of collaboration to aid school improvement and create a ‘self-improving school system’. However, collaboration between schools is patchy at best and it remains the case that headteachers are more likely to be in competition with each other than involved in collaboration for school improvement.

It is worth exploring why headteachers are reluctant to engage in school to school improvement initiatives despite of efforts by successive governments over the last 20 years to facilitate collaboration and system thinking.

Collaboration – Inevitable or Avoidable?:

In 2005, when I began my first headship, high quality educational leadership training was thin on the ground. I had completed the National Professional Qualification for Headship (NPQH), but at the time this was poor quality training (it is much better now). In an attempt to build the skills and knowledge needed to be effective in the role of a school leader, I undertook a doctorate in educational leadership and management. My research focused on ‘collaborative leadership and system improvement’. This area of research was interesting to me as I had noticed in my role as a deputy head leading on joint work between six local schools that the headteachers involved in the project found it difficult to work effectively in collaborative groups – in fact it seemed that some school leaders wanted to avoid any collaborative work at all.

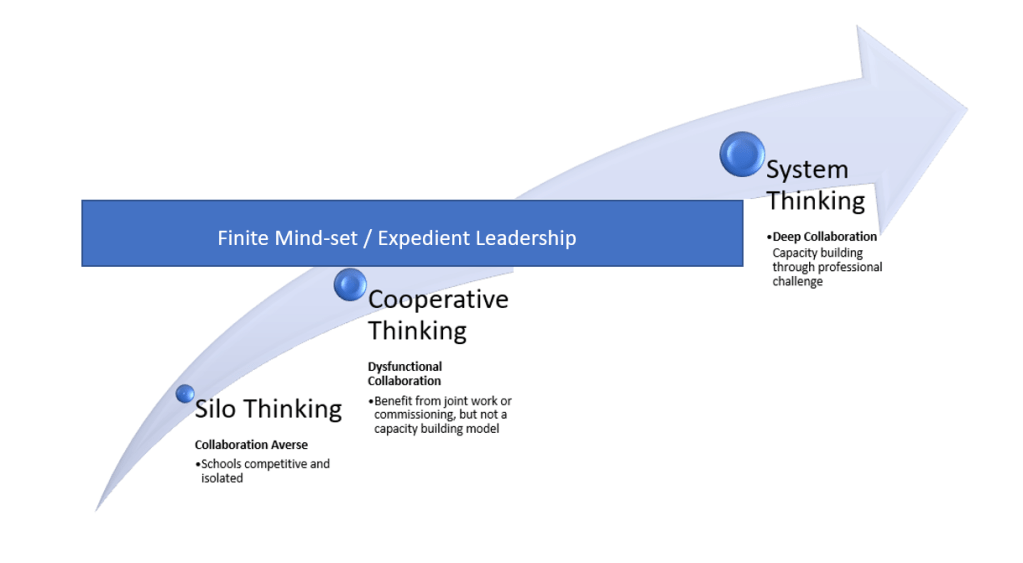

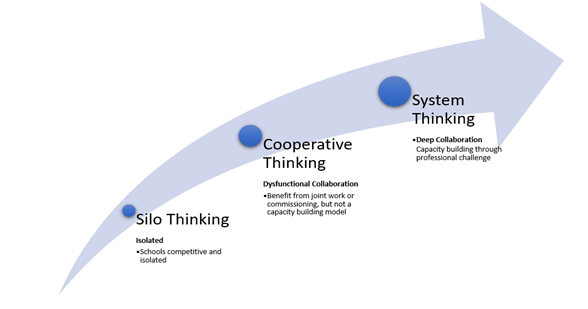

At the time (around 2001 – 2002), there was a move nationally towards higher levels of collaboration between schools. The National College of School Leadership (NCSL) attempted to facilitate this school collaboration by funding ‘networked learning communities’ (NLCs). These were a cluster of schools working in partnership to enhance the quality of pupil learning, professional development and school-to-school learning. NLCs were constructed to develop ‘deep collaboration’ between schools in the hope that this would build capacity and act as a vehicle for school improvement. It was hoped that by ‘incentivising’ collaboration, headteachers would begin to see each other as partners rather than seeing each other as competitors. The NLCs encouraged groups of local schools to research an agreed area of concern and work together on solutions with an aim to develop robust professional relationships across boundaries and between schools. Over time it was believed that the collaborative relationships that came about would become standard practice, enabling school leaders to work collaboratively to challenge one another, enquire into practice and build capacity that facilitated improved learning outcomes for staff and higher attainment for pupils. The NLCs were based on research about the widespread benefits of collaboration to school improvement, ‘Working smarter together rather than harder alone’, was the phrase at the heart of the initiative. It was hoped that these facilitated collaborative groups would form the basis of more permanent collaborative working and improved relational trust between headteachers. The diagram below (figure 1) shows the trajectory it was hoped the leadership thinking would take – from school improvement as an isolated ‘silo’ to seeing school improvement in terms of the wider educational system. The school where I was deputy was asked to facilitate this joint work between a group of six schools and I was tasked with arranging the NLC research topic and agreeing a timetable of joint meetings and school visits.

While extensive support was made available nationally for these NLCs (we were even given a budget of around six thousand pounds to support joint work), headteachers were reluctant to become involved. Actually, in some cases it was more than reluctance and some heads were disinclined to work jointly to the point of avoidance of the collaborative work – despite the fact there were potentially many benefits to participation, the NLCs were well researched, well financed and the implementation was supported by the DfE (called the DCSF at the time). I remember very clearly one headteacher turned up to the first meeting of the NLC and asked for ‘their share’ of the pot of money so they could leave and not have to be involved in any of the joint work the group of schools were undertaking. While this was quite an extreme view, it was clear that many of the other heads involved in the NLCs were not used to thinking in terms of school to school collaboration and were almost resentful of the efforts it was taking from focusing solely on their own school. The school leaders involved found it difficult to see how such joint work, sharing and collaborative investigation would be of benefit to their school.

The robust professional relationships and deep collaborative work between leaders and schools intended by the NLC initiative never eventuated within this NLC. In fact the joint work intended by the whole NLC initiative was resisted in the majority of cases and – while there were some excellent examples of collaboration work – the collaborative evolution of school improvement intended was never fully achieved.

I took this ‘headteacher avoidance’ of collaborative school improvement as a focus for my doctoral research.

The conclusions the the research into why collaborative school improvement was not widespread in education fell into the three main strands;

First, due to the high stakes accountability headteachers were reluctant to place effort and resources into initiatives that did not directly benefit their school. Additionally, when heads were facing challenging in school, collaborative activities were not seen as the most effective use of time. So rather than seeing collaboration as capacity building, headteachers saw it was a waste of resources – especially when the school was in a period of difficulty.

Second, was due to issues surrounding ‘headteacher identity’ – how headteachers are perceived and how they perceive themselves. Personal perceptions can have a huge impact on behaviours and attitudes. Headteachers have an idealised notion of ‘the successful head’ (in fact it’s why so many talk of the ‘imposter syndrome’). However, the ideal is hard to live up to every day and the research showed that many heads tend to ‘manage their image’ in a way that hid certain imperfections – maybe their lack of knowledge, that they needed help or that things in the school weren’t going well. So not only does high stakes accountability put pressure on headteachers to ‘get results’ and have a great Ofsted, there is also pressure to look successful and be seen as knowledgeable and in control. Living up to such idealised notion of ‘the perfect leader’ makes joint work, sharing and challenging professional relationships between school leaders highly unlikely as working closely with others makes keeping up the pretense impossible.

It is the second of these conclusions I will look at below (I will examine the impact of high stakes accountability in a later blog), in relation to how school leaders are perceived by others as well as how they perceive themselves and the impact this has on leadership thinking and behaviours – especially in relation to the levels of collaboration headteachers are willing to engage in between schools.

‘Collabor-haters’, Sios and Dysfunction:

Headteachers are recruited, developed and encouraged to be knowledgeable, independent, competitive and in control. The problem is that schools are incredibly complex environments – one person cannot know everything and constantly be in control. The great irony for many headteachers is they can never be what they were recruited to be, so they must maintain a constant illusion. I will look more closely at issues to do with identity later, but it is enough to say here that most headteachers try to live up to an idealised notion of a perfect headteacher – one with all the knowledge and answers and, most importantly, no weaknesses. Of course in order to maintain this illusion headteachers can never work too closely with other school leaders – as to do so would mean letting them in behind the mask and the illusion would be shattered.

The idealised conceptualisation of leadership means some school leaders are likely to reject collaboration and become what I have termed ‘collabo-haters’. They shun joint work and will not engage in projects of professional critique, collaborative enquiry or scrutiny and challenge from colleagues. In order to hide gaps in knowledge and any underperformance, some school leaders are more comfortable operating the school as an isolated ‘silo’ rather than joining together in a collaborative group that aims to deeply interrogate the performance of the school. This means that they can maintain the illusion, but it also means that they also avoid the critical / supportive feedback that can ultimately leads to significant school improvement.

It is not always possible for leaders to avoid collaboration and there will be some situations where school leaders are incentivised to collaborate (such as the NLCs mentioned earlier) or are brought together in partnerships – such as local authority groupings. However, it is rare that these incentivised or geographical groupings of schools produce the deep collaboration and robust challenging relationships. They are not full ‘collabor-haters’ – avoiding any joint work – instead they tend to engage in what I have termed ‘dysfunctional collaboration’. These school leaders will work together cooperatively to benefit from centrally held resources and joint commissioning initiatives – as long as there is something in it for them. They attend these collaborations to get, not to give or share. So they will purchase a joint resource or appoint a member of staff to work peripatetically between schools – but they do not build robust relationships designed to challenge thinking and established practice with a view to overall improvement. Dysfunctional collaboration gives the pretense of working with others, while keeping other school leaders at arm’s length. I will explore why headteachers will shun close scrutiny of their own leadership under a later heading ‘The Persistent Problems of Leadership’.

System Thinking:

It is common for those within education to talk of system thinkers and system leaders. System thinking was made popular decades ago by Peter Senge in his book ‘The 5th Discipline’. He refers to system thinking as;

“…a discipline for seeing wholes. It is a framework for seeing interrelationships rather than things, for seeing patterns of change rather than static ‘snapshots’.“

So a system thinker is someone who can see beyond the boundaries of their own institution to acknowledge how their own setting is linked to others through webs of interdependence. Collaboration, sharing and an understanding of the bigger picture is at the heart of system thinking.

System leadership then is the ability to lead a single organisation, while also being able to maintain a view on how links can be made to share and cooperate with others – in ways that bring benefits to all involved. System leaders are collaborative, able to build coalitions, invite feedback and welcome challenge. The most powerful thing about system leaders is that they build capacity for improvement in their own setting and in the wider system. As mentioned in a previous blog, system leaders are accountable for their own setting, but feel responsible for improvement in the wider system as well.

It has been hoped – expected even – that, given the right environment, there is a gradual move from silo thinking to system thinking in education and the development of a ‘self-improving school system’ will slowly evolve over time – as displayed in figure 1. But this has not been the case. There are too many elements within established education approaches that do not encourage school leaders to collaborate in a way that leads to system thinking. In fact the existing educational structures encourage leaders to focus on their own school – to operate as a ‘silo’ – with no incentive for taking a wider system view and working on deep collaboration with other schools. If a headteacher is going to place time, effort and resources into improvement activities, their focus will inevitably be their own setting. They are given no reason whatsoever to put the time, effort and resources into improvements that will benefit others in the wider system.

School leaders are motivated to improve the silo – not the system.

In a previous blog I spoke about the ‘anchor’ that prevents leaders from moving to an infinite mind-set. Many headteachers persist in focusing on short term goals, see other schools as competitors, identify some pupils as ‘undesirable’ and place unrealistic demands of staff. The focus on short term, finite goals means they become expedient in approach – choosing behaviours and actions that achieve short terms wins. It is this mind-set that prevents school leaders from evolving their thinking beyond low level dysfunctional collaboration to the more powerful, capacity building, system thinking. See figure 2 below.

I will return to the concept of ‘expedient leadership’ in more detail in a later blog, but it is important to say at this point that it is expedience that anchors thinking in terms of silos and collaborative dysfunction and prevents school leaders from the system thinking needed to harness the capacity building collaborative relationships that have the potential to produce a self-improving school system.